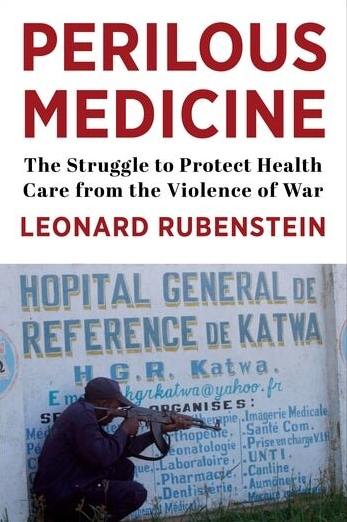

Pervasive violence against hospitals, patients, doctors, and other health workers has become a horrifically common feature of modern war. These relentless attacks destroy lives and the capacity of health systems to tend to those in need. Inaction to stop this violence undermines long-standing values and laws designed to ensure that sick and wounded people receive care. |

|

In his new book Leonard Rubenstein—a human rights lawyer who has investigated atrocities against health workers around the world and core faculty member at the Berman Institute of Bieoethics —offers a gripping and powerful account of the dangers health workers face during conflict and the legal, political, and moral struggle to protect them. In a dozen case studies, he shares the stories of people who have been attacked while seeking to serve patients under dire circumstances including health workers hiding from soldiers in the forests of eastern Myanmar as they seek to serve oppressed ethnic communities, surgeons in Syria operating as their hospitals are bombed, and Afghan hospital staff attacked by the Taliban as well as government and foreign forces. Rubenstein reveals how political and military leaders evade their legal obligations to protect health care in war, punish doctors and nurses for adhering to their responsibilities to provide care to all in need, and fail to hold perpetrators to account.

Bringing together extensive research, firsthand experience, and compelling personal stories, Perilous Medicine also offers a path forward, detailing the lessons the international community needs to learn to protect people already suffering in war and those on the front lines of health care in conflict-ridden places around the world.

In an interview with Global Health Now, Rubenstein explained why he wrote the book:

“I wrote it, first and foremost, for those who take enormous risks to provide care in the midst of war, so that their commitment to health can be matched by a commitment to rights to their protection. At the same time, I wanted to enhance understanding of the pervasiveness of the violence, the logics animating it, and its devastating impacts for millions of people already suffering in war. Another goal was to seek to engage the public health, nursing, and foreign policy communities—and the wider public—in stopping it.”

Read the full Q&A.

Listen to Rubenstein’s appearance on the “Public Health On Call” podcast.

Attend (via Zoom) his Oct. 11 Berman Institute Seminar Series talk, “The Paradoxical Fragility of the Norms of Protection of Health Care in War.”

Rubenstein has spent his career, spanning four decades, devoted to health and human rights. A graduate of Harvard Law School he is now Professor of the Practice at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and Director of the Program in Human Rights, Health and Conflict at its Center for Public Health and Human Rights. At Johns Hopkins, he is also a core faculty member of the Berman Institute of Bioethics and the Center for Humanitarian Health.