Searching for Winning Public Health Strategies in Lessons from the Covid War

At the beginning of 2021, Ruth Faden, founder of the Johns Hopkins Berman institute of Bioethics, joined 33 other leading national experts to form the Covid Crisis Group. The goal of the group was to lay the groundwork for a National Covid Commission, thinking that the U.S. government would soon establish a formal commission to study the biggest global crisis of the twenty-first century. So far, it has not.

In the face of this faltering political momentum—a void where there should be an agenda for change—the group decided to speak out for the first time. On Tuesday, April 25, they will publish Lessons from the Covid War (PublicAffairs), the first book to distill the entire Covid story from ‘origins’ to ‘Warp Speed.’ With the U.S. ending its formal declaration of a public health emergency earlier this month, this investigative report reveals what just happened to us, and why. Plain-spoken and clear-sighted, Lessons from the Covid War cuts through the enormous jumble of information to make some sense of it all.

“Our public health system was neither set up nor able to respond in the way the country needed, in part because of an antiquated division of labor in our federalist system,” said Faden, who chaired President Clinton’s Advisory Committee on Human Radiation Experiments.

“There was not, and still is not, any kind of centralized national mechanism for responding to massive but non-military threats like a pandemic or climate change. As a consequence, too often, states were left without adequate guidance and had to create regulations and policies on their own.”

During the pandemic, Faden co-led a multi-disciplinary team that created the eSchool+ Initiative to provide tools and resources regarding Covid policy for K-12 schools, as well as the COMIT project to track global vaccine policies for pregnant and lactating people. Since June, 2020 she has also served on the WHO SAGE Working Group on COVID-19 Vaccines that provides policy guidance on vaccine prioritization and use. Faden also helped lead a partnership between the Berman Institute and the SNF Agora Institute that in May 2020 published an ethics framework for the Covid reopening process.

The Covid Crisis Group is holding a discussion of its findings at the National Academy of Medicine on Monday, April 24, one day in advance of their report’s publication. Faden will moderate the session, “19th Century System Meets 21st Century Pandemic,” at 2:15 p.m. The entire discussion will be broadcast online here, starting at 12:30 p.m. Faden says topics from the book that her panel will address include not only what went wrong with our public health and health care systems but also what strategies need to be adopted, what needs to be changed or updated, so that both public health and healthcare will be fit for 21st century pandemic purposes.

“The United States, despite its great wealth, advanced science, and state of the art medical care didn’t handle Covid better than other countries and, in fact, did worse than most,” said Faden.

“The pandemic showed Americans that our scientific knowledge had run far ahead of our nation’s ability to apply it in practice. I hope this book will show how Americans can come together, learn hard truths, build on what worked, and prepare for global emergencies to come.”

GLIDE Project Launches Gateway Providing Access to Infectious Disease Ethics Research

Bioethics experts from Johns Hopkins University and the University of Oxford have collaborated with Wellcome Open Research to launch the Global Infectious Disease Ethics Collaborative (GLIDE) Gateway, a timely and critically important new hub for publishing open access, peer-reviewed articles focusing on ethics, infectious disease, and global health.

“The Gateway will enhance GLIDE’s capacity to provide a flexible collaborative platform for identifying and analyzing ethical issues arising in infectious disease treatment, research, response, and preparedness, through the lens of global health ethics. It serves as an inclusive space for diverse global perspectives, with particular attention to including the voices of researchers at all career stages,” said Jeffrey Kahn, Andreas C. Dracopoulos Director of the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics.

Predating the COVID-19 pandemic, bioethics colleagues from the Berman Institute and the Ethox Centre/Wellcome Centre for Ethics and Humanities at the University of Oxford realized the value that collaboration could add to analyzing ethical issues related to infectious disease research. Together, they established the Oxford-Johns Hopkins Global Infectious Disease Ethics Collaborative (GLIDE), funded by a Wellcome Humanitites and Social Science Awardbringing together scholars, trainees, and partners from around the world to undertake responsive research on pressing issues and forward-looking projects with longer timeframes.

The Gateway’s launch was announced during the opening remarks of “From Crisis to Wellbeing: Recognizing the Power and Potential of Global Health Ethics,” a GLIDE conference focused on advancing knowledge and capacity in global health ethics, exploring societal wellbeing and unity at the heart of global health ethics.

“When it comes to accessing academic journal literature, researchers can face significant challenges. Traditional journals often charge a fee to access research articles. This poses a barrier, especially for authors in low- and middle-income countries, and early career scholars.

The growth of open access publications has been a major step toward addressing this issue,” said Michael Parker, Ethox Cetnre Director.

“Thanks to open research, the bioethics research community can have immediate access to relevant research, expertise, and resources. This, in turn, can help inform responses related to ethical issues arising from public health emergencies in real-time.”

The GLIDE Gateway welcomes different research formats and outputs including Open Letters, opinion pieces, literature reviews, policy and conceptual analysis, empirical, normative, and policy research. An example of the impactful research hosted there include an Open Letter by Smith et al. in which a group of 17 experts in bioethics highlighted five key ethical lessons from the initial experience with COVID-19. This paper currently has over 6,600 views and 500 downloads.

The GLIDE Gateway launched in tandem with another Wellcome Open Research content hub dedicated to bioethics, the Epidemic Ethics Collection. Epidemic Ethics is a global community of bioethicists and stakeholders who are involved in public health and research responses to public health emergencies. Both portals welcome submissions from Wellcome Trust funded researchers.

eSchool+ Initiative Finds Widespread Discrepancies in School Covid Policies Between and Even Within Individual States

In an analysis of all 50 states’ policies about masking in schools, requiring COVID-19 vaccines for eligible students and teachers, and providing COVID-19 services in the school setting, Johns Hopkins University researchers have found widespread discordance and variation not only between states but also within states themselves as individual districts adopt policies at odds with their own governors’ guidelines.

“The COVID-19 virus doesn’t care about school district or state lines. The current uncoordinated approach has us in a third year of schooling impacted by coronavirus and we’re rapidly closing in on a fourth,” said Megan Collins, a bioethicist and associate professor of medicine at the Wilmer Eye Institute who co-directs the Johns Hopkins Consortium for School-Based Health Solutions. “Our goal is to provide useful, reliable information for education and public health policy stakeholders and researchers, teachers, school staff, and parents from across the country – anyone working on or thinking about kids going back to school and staying there.”

The analysis utilizes information from a new online tracker that examines state policies about masking in schools, COVID-19 vaccines for eligible students and teachers, and COVID-19 services offered in the school setting in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, the Bureau of Indian Education, and major U.S. territories. The tracker also includes details from 56 index school districts selected from 20 states, representing the lowest and highest poverty, as well as the largest school district in each state.

Currently, the tracker lists North Dakota as the only state that prohibits individual districts from requiring masks in school. Similar mask mandate bans in Florida, Oklahoma are on hold, awaiting the outcome of lawsuits seeking to overturn them. South Dakota and Oklahoma prohibit a vaccine mandate. But the JHU researchers found marked variations at the district level, identifying 46 instances where district policies for masking or vaccination did not align with their state’s policy.

“The disconnect between state and district policy can create issues of trust for parents and teachers, as they being told one thing by the state, and often something entirely different by their school district,” said Collins. The tracker also includes information about school-based testing and vaccination availability, and if virtual/hybrid learning options are offered for students based on the state or district mask or vaccination policies.

“While all children have suffered from in this pandemic, disadvantaged children have suffered the most. However, on mask and vaccine policies, the biggest differences seem to by size of school district, rather than poverty or affluence,” said Ruth Faden, founder of the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics. “We found that the largest districts are requiring masks and teacher vaccination at much higher levels than smaller districts, regardless of poverty level.”

The study also found that, as with other pandemic policies, who is in the governor’s mansion matters. While 65 percent of states with Democratic governors require teacher and student masking, only 10 percent of states with Republican governors do. Similarly, 31% of states with Democratic governors require teacher COVID-19 vaccination; three percent of states with Republican governors do.

“The team’s work is designed to bring attention to the accumulating body of data about school COVID-19 policies, and to examine which policies risk to worsen existing inequities in access to educational resources,” said Annette Campbell Anderson, Deputy Director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Safe & Healthy Schools and a professor in the School of Education.

“We want to share the pulse of what’s happening across the country as policymakers analyze the landscape for 2022 and think about appropriate actions.”

Join the Berman Institute at ASBH 2021

The Berman Institute will be well represented at the 23rd annual meeting of the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities (ASBH), with a group of faculty, fellows, and students scheduled to present online.

View the full schedule and summaries of all Berman Institute presentations.

|

You can also follow us on Twitter: #ASBH21, featuring our @bermaninstitute, @aregenberg, @kahnethx, @tnrethx, and more. |

Eyeglasses for School Kids Boosts Academic Performance

Students who received eyeglasses through a school-based program scored higher on reading and math tests, Johns Hopkins researchers from the Wilmer Eye Institute and School of Education found in the largest clinical study of the impact of glasses on education ever conducted in the United States. The students who struggled the most academically showed the greatest improvement.

The study, with implications for the millions of children who suffer from vision impairment but lack access to pediatric eye care, was published Sept. 9, 2021, by JAMA Ophthalmology.

“We rigorously demonstrated that giving kids the glasses they need helps them succeed in school,” said senior author Megan Collins, a pediatric ophthalmologist at the Wilmer Eye Institute, associate faculty at the Berman Institute of Bioethics, and co-director of the Johns Hopkins Consortium for School-Based Health Solutions. “This collaborative project with Johns Hopkins, Baltimore City and its partners has major implications for advancing health and educational equity all across the country.”

The team studied students who received eye examinations and glasses through the Vision for Baltimore program, an effort launched in 2016 after Johns Hopkins researchers identified an acute need for vision care among the city’s public school students: as many as 15,000 of the city’s 60,000 pre-K through 8th-grade students likely needed glasses though many didn’t know it or have the means to get them.

Vision for Baltimore, which is beginning its sixth year, is operated and funded in partnership with the Johns Hopkins schools of Education and Medicine, Baltimore City Public Schools, the Baltimore City Health Department, eyewear brand Warby Parker, and national nonprofit Vision To Learn. The Baltimore health department conducts screenings, Vision To Learn performs eye exams and Warby Parker donates the glasses. In addition to providing more than $1 million in support, Johns Hopkins works closely with the program team to provide technical assistance.

In five years Vision for Baltimore has tested the vision of more than 64,000 students and distributed more than 8,000 pairs of glasses. The Johns Hopkins study is the most robust work to date evaluating whether having glasses affects a child’s performance in school.

The three-year randomized clinical trial, conducted from 2016 to 2019, analyzed the performance of 2,304 students in grades 3 to 7 who received screenings, eye examinations and eyeglasses from Vision for Baltimore. The team looked at their scores on standardized reading and math tests, measuring both 1-year and 2-year impact.

Reading scores increased significantly after one year for students who got glasses, compared to students who got glasses later. There was also significant improvement in math for students in elementary grades.

Researchers found particularly striking improvements for girls, special education students, and students who had been among the lowest performing.

“The glasses offered the biggest benefit to the very kids who needed it the most – the ones who were really struggling in school,” Collins said.

The overall gains for students with glasses were essentially equivalent to two to four months of additional education compared to students without glasses, said lead author Amanda J. Neitzel, deputy director of evidence research at the Johns Hopkins Center for Research and Reform in Education. For students performing in the lowest quartile and students participating in special education, wearing glasses equated to four to six months of additional learning—almost half a school year.

“This is how you close gaps,” Neitzel said.

The academic improvements seen after one year were not sustained over two years. Researchers suspect this could be a result of students wearing their glasses less over time, possibly due to losing or breaking them.

To maintain the academic achievement, the researchers say in addition to providing the initial exams and glasses, school-based vision programs should develop stronger efforts to make sure children are wearing the glasses and to replace them if needed.

“This study, grounded in thorough and rigorous research, has proven our most fundamental assumption in launching Vision for Baltimore six years ago – that providing kids glasses in their schools will significantly improve academic success,” said Johns Hopkins President Ron Daniels. “These results validate the dedication of all of the program’s committed partners, from the principals, staff and teachers across Baltimore City schools to the optometrists at Vision to Learn and the school vision advocates from Johns Hopkins. Looking forward, we hope to work with our state and city leaders to ensure that this impactful program has sustainable funding for years to come.”

Global Policies on COVID-19 Vaccination in Pregnancy Vary Widely by Country

Although pregnant people are at elevated risk of severe COVID-19 disease and death, countries around the world vary widely in their policies on COVID vaccination in pregnancy, with 41 countries recommending against it. Ninety-one countries have policies that allow for at least some pregnant people to receive COVID vaccines – 45 of which broadly permit or recommend vaccines in pregnancy – according to Johns Hopkins University’s COVID-19 Maternal Immunization Tracker (COMIT), a newly launched online resource providing a global snapshot of public health policies that shape access to COVID-19 vaccines for pregnant and lactating people.

“Data about COVID vaccines’ safety for pregnant people and their offspring have generally been reassuring. But countries around the world have taken a variety of positions on COVID vaccination and pregnancy — ranging from highly restrictive policies that bar access to vaccines, to permissive positions in which all pregnant or lactating people can receive vaccine and, in some cases, are recommended and encouraged to do so,” said Ruth Karron, Director of the Center for Immunization Research at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and a professor in the School’s Department of International Health.

COMIT is the first resource that provides a global snapshot of public health policies that influence access to COVID-19 vaccines for pregnant and lactating people, enabling users to explore policy positions by country and by vaccine product. Through maps, tables, and country profiles, COMIT provides regularly updated information on country policies as they respond to the dynamic state of the pandemic and emerging evidence.

“This is an extremely valuable resource for anyone concerned with the health of pregnant women and their offspring anywhere in the world. By compiling and updating countries’ policy positions regarding COVID-19 vaccination for pregnant and lactating people, COMIT makes it possible to track at a glance the ongoing global changes in this rapidly changing sphere,” said Alejandro Cravioto, Chair of SAGE, the international panel of experts making COVID-19 vaccine recommendations to the World Health Organization.

In the past month alone, seven countries have joined the ranks of those with policies recommending COVID-19 vaccination for pregnant and lactating people.

“The variability in policy positions is in part a consequence of the absence of evidence on vaccines in pregnancy, because pregnant and lactating people are excluded from the vast majority of clinical trials. As a result, public health authorities and recommending bodies are developing guidance on COVID vaccines and pregnancy with far less evidence than they have for most other populations,” said Ruth Faden, founder of the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics.

“Our hope is that COMIT might convince policy makers worldwide to expand access to vaccination for pregnant people. We are seeing some momentum in that direction, but we need to see more.”

The COMIT team notes that varying policies regarding vaccination of pregnant people could have serious implications for gender equity in the global rollout of COVID-19 vaccines, including among the high-priority group of health workers who would otherwise be first in line to receive vaccine.

“In many countries, the health system is hugely dependent upon female health workers in their reproductive years, many of whom are pregnant or breastfeeding. If they cannot be adequately protected from serious COVID-19 disease or death, it would not only be a threat to a gender-inclusive response, but potentially set back the health system during a crucial time in the response and for years to come,” said Carleigh Krubiner, a Berman Institute faculty member and a policy fellow at the Center for Global Development.

COMIT’s interactive global map conveys at a glance whether pregnant or lactating individuals are allowed or encouraged to receive any vaccine currently authorized for use in individual countries. Other features include:

- Tables that enable visitors to compare vaccine policies across countries, including any special requirements (e.g. a doctor’s note), with various sort and filter features to understand how individual country policy positions compare across geography and vaccine products.

- Maps that filter by product and policy position, with an easy toggle between pregnancy and lactation to see how recommendations differ for pregnant and breastfeeding individuals

- Individual country pages that give a detailed account of policy positions, and changes over time, and provide links to source documents.

“The COMIT website will be an invaluable source of information for policymakers around the world as the COVID-19 vaccine rollout continues,” said Chizoba Barbara Wonodi, a faculty member in the International Health department at the Bloomberg School and Nigeria Country Director at the School’s International Vaccine Access Center. “Even as the COVID vaccination rate in the United States approaches 50 percent, only about six percent of the world’s population has been fully vaccinated to date. This inequity in access needs urgent global attention.”

The COMIT policy tracker was developed by members of the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics and the Johns Hopkins Center for Immunization Research, with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Wellcome.

Kadija Ferryman, PhD

New Global Tracker to Measure Pandemic’s Impact on Education Worldwide

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted education for 1.6 billion children worldwide over the past year. To help measure the ongoing global response, Johns Hopkins University, the World Bank, and UNICEF have partnered to create a COVID-19 – Global Education Recovery Tracker.

Launched today, the tool assists countries’ decision-making by tracking reopening and recovery planning efforts in more than 200 countries and territories.

The effort captures and showcases information across four key areas:

- Status of schooling

- Modalities of learning (remote, in-person or hybrid)

- Availability of remedial educational support

- Status of vaccine availability for teachers

The Global Education Recovery Tracker seeks to build upon Johns Hopkins University’s pivotal work in gathering quality data on COVID-19 cases, testing, and vaccinations, along with the strategic roles that the World Bank and UNICEF play in operational and policy support to countries during the pandemic.

“Throughout the pandemic Johns Hopkins has demonstrated the vital role for universities in providing accurate, evidence-based data and information for the world,” said Johns Hopkins Provost and Senior Vice President for Academic Affairs Sunil Kumar. “We hope the work of this partnership will build understanding of how COVID-19 continues to affect students everywhere.”

Data through early March 2021 show that 51 countries have fully returned to in-person education. In more than 90 countries, students are being instructed through multiple modalities, with some schools open, others closed, and many offering hybrid learning options.

Regionally, there are emerging indications of shifts in learning modalities. Remote learning continues to dominate in the Middle East and North Africa where schools were largely closed in recent weeks. However, in Sub-Saharan Africa, most students are physically attending school. In the East Asia and Pacific region, in-person education has mostly resumed, with stringent social distancing measures. The regions of South Asia, Central Asia, and Europe are mainly relying on hybrid education where the infrastructure allows. Across Latin America, countries are using mixed approaches that include remote, hybrid, and in-person education. However, the majority of schools remain partially or fully closed to in-person classes with remote education as the most used modality.

“The world was facing a learning crisis before COVID-19,” said Jaime Saavedra, World Bank Global Director for Education. “The learning poverty rate – the proportion of 10-year-olds unable to read a short, age-appropriate text – was 53% in low- and middle-income countries prior to COVID-19, compared to only 9% for high-income countries. A year into the pandemic, continued disruptions to schooling, shifts in learning modalities, and concerns for students’ well-being are ever greater, and this learning crisis is getting worse. COVID-19 related school closures are likely to increase learning poverty to as much as 63%.”

Saavedra emphasized the importance of this Tracker, “In many countries, students and teachers need urgent supplemental support. The return to school requires accelerated, remedial, and hybrid learning, as well as other interventions. Collecting and monitoring this data on what countries are doing is critically important to help us understand the magnitude of what support is needed as we go forward, learning from the major trends observed among countries.”

In addition to tracking the operational status of schools, the Tracker will also monitor how students are being supported. This includes changes to the school year schedule, tutoring, and remediation, especially for the primary school grades. These interventions will be a critical component of the education recovery process after a year that has affected the learning and well-being of 95% of school children across the globe.

In countries where the COVID-19 vaccine is available, the tool is tracking whether teachers are eligible as a priority group. As of early March, teachers are largely not being immunized as a priority group in low- and low-middle-income countries. Of the 130 countries where vaccine information was available, more than two-thirds are not currently vaccinating teachers as a priority group.

“Even as vaccines are beginning to rollout worldwide, for hundreds of millions of the world’s schoolchildren, the consequences of this pandemic are far from over,” said UNICEF Chief of Education Robert Jenkins. “We must prioritize the reopening of schools, including prioritizing teachers to receive COVID-19 vaccines once frontline health personnel and high-risk populations are vaccinated. While such decisions ultimately rest with governments making difficult tradeoffs, we must do everything in our power to safeguard the future of the next generation. And this begins by safeguarding those responsible for opening that future up for them.”

The Tracker is intended to offer evidence that informs policy makers and researchers working on COVID-19 responses. The tool is built to have the flexibility to incorporate emerging issues while offering a time trend of actions in the past months.

###

The Johns Hopkins University eSchool+ Initiative is a collaboration between the Consortium for School-Based Health Solutions, the Berman Institute of Bioethics, and the Johns Hopkins Schools of Education, Medicine, and Public Health. The eSchool+ Initiative focuses on child well-being from an equity lens, developing tools and resources for K-12 schools to help policy makers and educators support students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For more information about the eSchool+ Initiative, please visit: https://equityschoolplus.jhu.edu.

States Must Implement Teacher Vaccination Plans and Tracking to Ensure Safe School Reopenings

Even as President Biden this week urged states to prioritize teachers for vaccinations, an analysis conducted with Johns Hopkins University’s teacher vaccination tracker, launched today, shows no correlation between states’ school reopening status and the ability for teachers to get vaccinated against COVID-19. And no states are reporting the percentage of teachers and school staff that have been vaccinated.

“There is an accumulating body of scientific evidence that should be reassuring the public that kids can be brought back to school safely when appropriate mitigation measures are in place and community transmission is low. Right now, there is a massive disconnect between where schools are open and whether or not teachers have been prioritized for vaccination,” says Megan Collins, co-director of the Johns Hopkins Consortium for School-Based Health Solutions, who helped create the new eSchool+ Teacher & School Staff COVID-19 Vaccination Dashboard, which provides state-by-state information on school reopening status, teacher vaccination policies, and other vital data.

The new dashboard compiles data that will be essential to education and public health policy makers, teacher and school staff, and parents in making informed decisions about safe school reopening. In addition to monitoring state-by-state school reopening status, and vaccination prioritization for teachers and school staff, the dashboard includes a wide range of epidemiological data, including trends in cases, infection rate, and hospitalizations. It is updated at least twice weekly with publicly available information from state and territory departments of education, health, state COVID-19 dedicated websites, and news sources.

“More and more teachers will be eligible for vaccine over the coming weeks. There are many reasons why it is important that all or at least most teachers seize that opportunity and get vaccinated, including helping to build trust in vaccination in the wider school community,” said Ruth Faden, Founder of the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics.

The dashboard also monitors whether a state is making COVID-19 vaccination compulsory for teachers to return to in-person instruction, and if a state is monitoring uptake of vaccines by teachers/school staff, including acceptance and refusal rates, data that is not currently being tracked anywhere else. Monitoring vaccine acceptance rate will be a critical next step as vaccines become more readily available for teachers. To date, no states are reporting this information, says Faden.

“While many well-resourced parents are trusting the reopening process, other families are saying we’re not sure our children will be safe in schools. The question is not, who is sending their kids back, the question is who is not?” said Annette Campbell Anderson, deputy director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Safe and Healthy Schools and an assistant professor and faculty lead in the university’s School of Education.

“The information from this dashboard will provide data that will help rebuild trust among all families and will play an important role in achieving the ambitious, but realistic, goal of having all children back in schools by next fall.”

Collins said student learning loss must be top of mind for everyone.

“Recognizing the deleterious effect of lost learning over the past 12 months, especially for students from disadvantaged backgrounds, our efforts must be directed towards getting children back in the classroom this spring and next fall,” said Collins, who is also an assistant professor at the Wilmer Eye Institute and Berman Institute of Bioethics. “Many people assume that things will be back to normal in time to start the next school year, but it’s going to take an immense amount of work to make that happen.”

The eSchool+ Initiative is a collaboration between the Consortium for School-Based Health Solutions, the Berman Institute of Bioethics, the Rales Center for the Integration of Health and Education, and the Johns Hopkins schools of Education, Medicine, and Public Health. The Initiative develops tools and resources for K-12 schools to consider when and how to ethically reopen and close during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Government Leaders Should Not Skip to the Front of the COVID-19 Vaccine Line

Government leaders should not be allowed to move to the front of the line for COVID-19 vaccinations unless the criteria for such prioritization is well reasoned, clearly articulated in advance, and transparently applied, according to a new commentary published January 21 in The New England Journal of Medicine by a trio of Johns Hopkins University faculty.

There must be clear justification and explanation for why elected officials should be vaccinated before such high-priority groups as health care personnel, first responders, long-term care facility residents, critical infrastructure workforce, and those at increased risk for severe COVID-19, according to the authors of the article “Who Goes First? Government Leaders and Prioritization of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines.”

“In all the planning, discussion and establishment of priority tiers, there was no early prioritization for government officials, so their being among the very first people vaccinated makes it look like they jumped the queue,” said Jeffrey Kahn, Andreas C. Dracopoulos Director of the Berman Institute of Bioethics, who co-authored the article with Profs. Mark T. Hughes and Allen Kachalia.

“We’re then faced with the perception of government leaders saying ‘Do as we say, not as we do,’” added Dr. Kachalia, Senior Vice President of Patient Safety and Quality for Johns Hopkins Medicine.

The article notes that few nationally recognized prioritization frameworks grant government leaders priority status: “Whether they must work in settings posing higher transmission risk is debatable at best, and they can protect themselves from exposure in ways health care workers cannot.”

Government officials undoubtedly fulfill roles important to societal functioning, but vaccination recommendations developed by the CDC and other national groups place them in Phase 2, after higher risk groups. Non–risk-based factors that merit consideration for their prioritization include ensuring government stability, maintaining national security, and instilling public confidence in vaccination. Whether publicly receiving vaccination “will generate support for vaccination is uncertain and may not justify diverting vaccines from high-risk populations,” write the authors.

“Providing vaccine first to government officials without clear guidelines can undermine public trust in the rules that were put forward for all members of our society,” said Dr. Hughes, a faculty member at the Berman Institute and JHU School of Medicine, as well as co-chair of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Ethics Committee.

Any prioritization of government leaders requires clear articulation of why their incapacitation from COVID would be a serious threat to society. Additionally, it would need to be shown why a leader’s role renders protective measures other than vaccination to be impractical or ineffective.

“Public health officials making vaccine-distribution decisions should be impartial and apply allocation criteria uniformly, while aiming to mitigate health inequities,” say the authors. “Letting government officials jump the queue suggests that they’re more important than other members of society and that the rules don’t apply to them.”

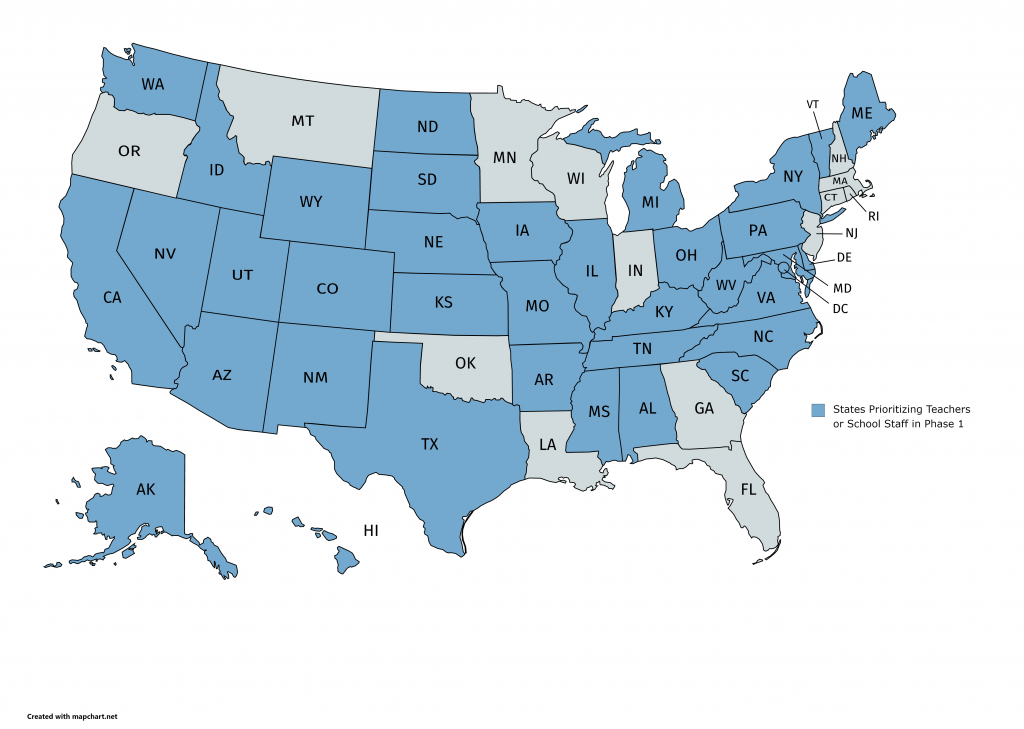

How Are Teachers Prioritized for COVID-19 Vaccination by the US States?

How are Teachers Prioritized for COVID-19 Vaccination by the US States?

Matthew A. Crane, Ruth R. Faden, Megan E. Collins

This post reflects information on vaccination planning collected on January 12, 2021.

As states contend with limited initial supply of COVID-19 vaccines, prioritization decisions are being made about local distribution. Many current prioritization decisions reflect guidance from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), as well as the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). However, the states have the authority to allocate vaccine as they see fit. Currently available state planning is highly dynamic, and subject to change.

One priority group for vaccination, teachers, has been the subject of scrutiny in recent weeks, with some education groups advocating that teachers and school staff be moved up in prioritization plans, relative to other groups. Because of this advocacy, and especially ACIP’s recent decision to recommend teachers and school staff for Phase 1b of vaccination, states that do not currently include the K-12 workforce in Phase 1 may reconsider their current prioritization.

In order to understand where teachers and school staff stand in current vaccination plans, we conducted an analysis of available COVID-19 vaccination planning from all fifty States and Washington D.C. For this search, we used the most-recent available information from state websites or health agencies about Phase 1 prioritization. Keywords for inclusion included “teachers,” “school staff,” and “education.” For each jurisdiction with available data in planning documents, we collected information about the subphase in which teachers or school staff are listed, as well as the exact language used. Sources included for this analysis are available in the Appendix.

As of January 12, 2021, 37 of 51 jurisdictions include teachers and/or school staff in vaccination planning for Phase 1 vaccination (Table 1). Language varies widely between jurisdictions, with exact language presented in Table 2. Teachers are most commonly prioritized in Phase 1b. Utah was the only state to have an undivided Phase 1 among these 37, and in that state teachers were included along with multiple other groups of high risk and essential workers. These results show an increase from an earlier collection of plans on December 19, 2020, where we found that only 23 of 51 jurisdictions prioritized teachers and/or school staff for Phase 1 vaccination.

Table 1: Phase 1 Prioritization of Teachers and School Staff in the United States (as of 1/12/21)

| Subphase | # of Jurisdictions | Jurisdictions Prioritizing Teachers for Phase 1 |

| Phase 1 | 1 | UT a |

| Phase 1a | – | No States |

| Phase 1b | 34 | AL, AK, AZ, AR, CA, CO, DE, HI, ID, IL, IA, KS, KY, ME, MD, MI, MS, MO, NE, NV, NM, NY, NC, ND, OH, PA, SC, TN, TX, VT, VA, DC, WA, WY |

| Phase 1c | – | No States |

| Phase 1d | 2 | SD, WV |

a Utah has no Phase 1 subphase listed for teachers

These findings have limitations. They are limited to published prioritization information on government websites (recently updated full state plans, webpages, and phase 1-specific documents). We did not analyze all sources available, such as meeting minutes or recordings of ongoing discussions, or secondary sources such as news coverage. Additionally, state vaccination plans are being updated frequently, and may change in response to additional CDC guidance based on recent ACIP recommendations. Due to these limitations, caution should be exercised in interpreting the prioritization decisions from states which have not updated guidance documents recently. Furthermore, some states have not yet made their guidance on teacher sub-phase explicit. In these instances, our categorizations are based on best estimates of Phase 1 sub-phases from currently available information

Table 2: Jurisdictions Prioritizing Teachers for Phase 1 Vaccination (as of 1/12/21)

| Jurisdiction | Subphase | Language about Teachers | Sources

(version, date last updated if available) |

| Alabama | 1b | “Education sector (teachers, support staff members)” | Vaccination Allocation Plan

(1/11) |

| Alaska | 1b | “Education (Pre K-12 educations and school staff)” | Vaccine Allocation Guidelines

(1/4) |

| Arizona | 1b | “Education (K-12) and childcare workers” | County Health Department Website |

| Arkansas | 1b | “Teachers and school staff” | State Health Department Website |

| California | 1b | “Education” | State Website |

| Colorado | 1b | “Frontline essential workers in Education” | State Website |

| Delaware | 1b | “Education (teachers, support staff, daycare)” | State Vaccination Playbook

(1/7) |

| Hawaii | 1b | “Teachers and childcare and educational support staff (childcare, early education, K-12, post-secondary)” | State Plan Executive Summary |

| Idaho | 1b | “Pre-K-12 school staff and teachers and daycare [childcare] workers” | Advisory Committee Slides

(12/9) |

| Illinois | 1b | “Education (Congregate Child Care, Pre-K through 12th grade): Teachers, Principals, Student Support, Student Aids, Day Care Workers.” | State Website |

| Iowa | 1b | “Teachers/school staff” | State Vaccination Strategy

(V2, 12/4) |

| Kansas | 1b | “K-12 and Childcare Workers, including teachers, custodians, drivers and other staff” | Vaccine Prioritization Plan (1/7) |

| Kentucky | 1b | “K-12 School Personnel” | Vaccine Phases Update

(1/4) |

| Maine | 1b | “Education sector (teachers, and support staff) | State Website

(1/12) |

| Maryland | 1b | “Education, including K-12 teachers, support staff, and daycare providers” | Vaccine Distribution Announcement

(1/8) |

| Michigan | 1b | “School and child care staff” | Prioritization Guidance

(1/6) |

| Mississippi | 1b | “K-12 Teachers/Staff; College/University Teachers/Staff” | State Website |

| Missouri | 1b | “Teachers & Education Staff” | State Website |

| Nebraska | 1b | “Education (teachers, support staff, daycare)” | State Website |

| Nevada | 1b | “Educators in pre-school and K-12 settings, including teachers, aides, special education and special needs teachers, ESOL teachers, and para-educators; workers who provide services necessary to support educators/students, including but not limited to administrators, administrative staff, IT staff, media specialists, librarians, guidance counselors, essential workers in the Nevada Dept. of Education, etc.; workers who support the transportation and operational needs of school settings, including bus drivers, crossing guards, cafeteria staff, cleaning and maintenance staff, and bus depot and maintenance staff.” | State Playbook

(V3, 1/11) |

| New Mexico | 1b | “Early education and K-12 educators/staff” | State Website |

| New York | 1b | “P-12 school or school district faculty or staff (includes all teachers, substitute teachers, student teachers, school administrators, paraprofessional staff and support staff including bus drivers)

Contractors working in a P-12 school or school district (including contracted bus drivers)” |

State Website |

| North Carolina | 1b | “Education Sector (teachers and support staff members)” | State Website |

| North Dakota | 1b | “Workers employed by preschools or Kindergarten through 12th grade: Teachers, nutritional services, aides, bus drivers, principals, administrative staff, custodians, etc.” | State Website |

| Ohio | 1b | “Adults/employees in all schools that want to go back, or to remain, educating in person.” | State Website |

| Pennsylvania | 1b | “Education workers” | State Website |

| South Carolina | 1b | “Those who work in the educational sector—teachers, support staff, and daycare workers” | State Website |

| South Dakota | 1d | “Teachers and other school/college staff” | State Website |

| Tennessee | 1b | “Childcare, pre-school, and kindergarten through twelfth grade teacher, school staff, and school bus drivers” | Vaccination Plan (V3, 12/30) |

| Texas | 1b | “Teachers and school staff who ensure that Texas children can learn in a safe

Environment” |

Phase 1B Guidance |

| Utah | 1 | “K-12 teachers and school staff” | State Website |

| Vermont | 1b | “Education Sector” | Vaccination Plan

(V2, 12/28) |

| Virginia | 1b | “Childcare/PreK-12 Teachers/Staff” | State Website |

| Washington D.C. | 1b | “School teachers and staff” | Phase 1 Guidance

(12/28) |

| Washington | 1b | “K-12 educators and staff during in-person schooling” | Guidance Summary (1/7) |

| West Virginia | 1d | “Higher education and K-12 Faculty and Staff” | State Website |

| Wyoming | 1b | “K-12 Education (teachers and support staff)” | Vaccination Priorities

(12/30) |

Acknowledgement:

The structure of this analysis was inspired by the work of the Prison Policy Initiative on tracking incarcerated people and corrections staff in vaccination plans.

Appendix: Sources for Information on Prioritization of Teachers and School Staff for Phase 1 of COVID-19 Vaccination