Laurence B. McCullough, PhD, is Distinguished Emeritus Professor of Medicine and Medical Ethics at Baylor College of Medicine and held appointments on the medical and philosophy faculties at Texas A&M University from 1976-1979 and Georgetown University from 1979-1988. His areas of expertise include clinical ethics and ethics consultation, medical professionalism, ethics and obstetrics and gynecology, and the history of medicine.

Explore the Collection

- Anita Allen, JD, PhD

- Lori Andrews, JD

- George Annas, JD, MPH

- Margaret P. Battin, PhD

- Tom L. Beauchamp, PhD

- Arthur L. Caplan, PhD

- Alexander Capron, LLB

- R. Alta Charo, JD

- James F. Childress, PhD

- Larry Churchill, PhD, MDiv

- Robert Cook-Deegan, MD

- Rebecca Dresser, JD, MS

- Ruth R. Faden, PhD, MPH

- Alan Fleischman, MD

- Norman Fost, MD, MPH

- Vanessa Northington Gamble, MD, PhD

- Samuel Gorovitz, PhD

- Brad Gray, PhD

- Patricia King, JD

- Loretta M. Kopelman, PhD

- Bernard Lo, MD

- Ruth Macklin, PhD

- Laurence B. McCullough, PhD

- Gilbert Meilaender, PhD, MDiv

- Steven Miles, MD

- Jonathan Moreno, PhD

- Thomas H. Murray, PhD

- Susan Sherwin, PhD

- LeRoy Walters, BD, MPhil, PhD

- Rueben Warren, DDS, DrPH

- Daniel I. Wikler, PhD

- William J. Winslade, JD, PhD

- Laurie Zoloth, PhD

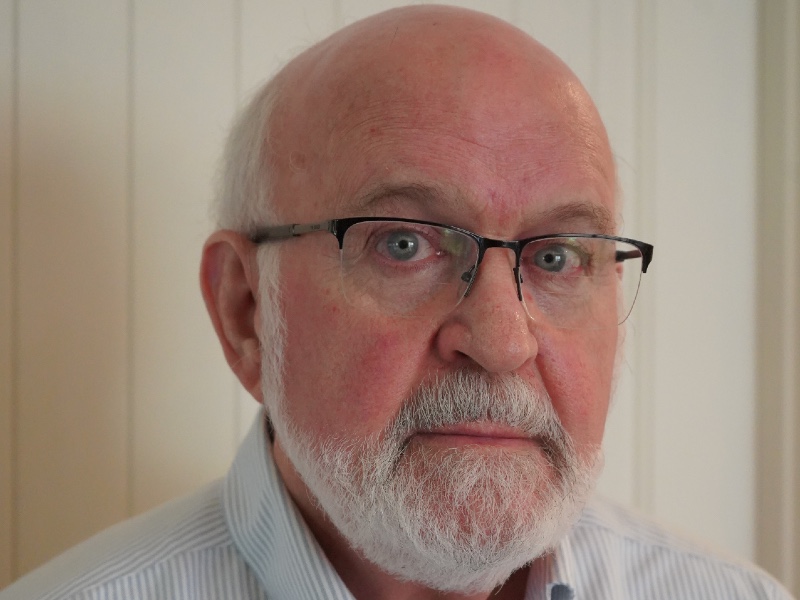

Laurence B. McCullough, PhD

Laurence B. McCullough, PhD

Distinguished Emeritus Professor of Medicine and Medical Ethics,

Baylor College of Medicine

You can find full audio, transcript, and other materials in the Moral Histories Archive.

Johns Hopkins University holds all rights, title, and interests to these records, including copyright and literary rights. The records are made available for research use. Any user seeking to publish part or all of a record in this collection must seek permission from the Ferdinand Hamburger University Archives, Sheridan Libraries.